Extracurriculars can broaden the path in

This is post 3 of 9 (I expect) examining lessons from this paper on college admission by Raj Chetty, David Deming, and John Friedman. In the first two posts, we considered how income affects admission rates at the most elite private colleges but not selective state schools.

Now we’re going to focus on how applicants from high-earning families get in at higher rates: high non-academic ratings, feeder schools, and legacy preference. I’m starting will non-academic ratings because it is the most modifiable of those factors. You, as a parent, can’t wave a magic wand and get your kid into Sidwell Friends or change your alma mater. But you can help your kid earn a high non-academic rating.

Chetty et al. figure that income preferences at the most prestigious and selective schools in the country mean that an incoming freshman class at one of these schools has 103 “extra” kids from the top 1% of the income distribution. That is, if these colleges turned off the preferences that give those very rich kids an advantage, there would be 103 fewer of them in an imaginary 1650-person class at Stanvard.

Of those 103 “extra” rich kids, Chetty and his coauthors figure 25 of them get in because they’re recruited athletes, 47 because of legacy preferences, and 31 because of their high non-academic ratings.

What money can and can’t buy

When colleges are rating applicants, they assign multiple scores. At Harvard, those scores are athletic, extracurricular, academic, personal, and an overall one. This Chetty paper is consistent with my understanding that other colleges have roughly similar systems.

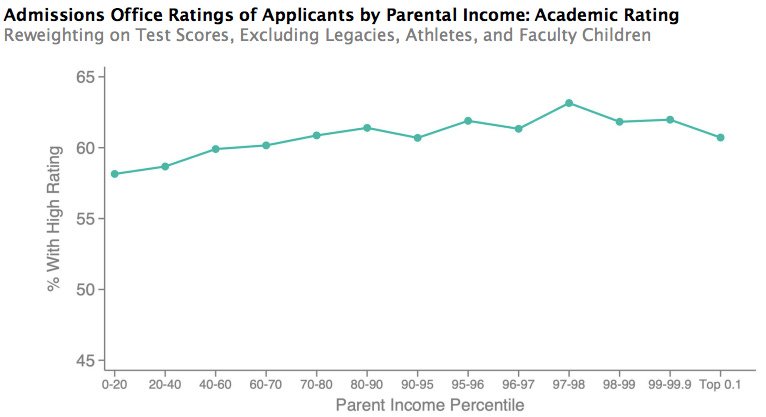

This new paper shows that rich families can’t do much to improve the academic ratings their kids get. Even though Kaplan claims otherwise, test prep doesn’t improve standardized test scores by much. Hundreds of thousands of high schoolers in the country, not just the richest ones, can earn an impressive transcript by taking AP, IB, or community college classes. The line below is pretty flat.

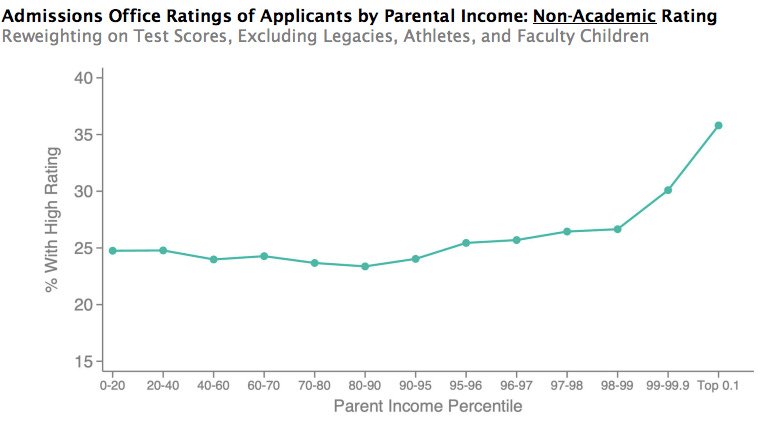

The distribution of non-academic ratings, which is essentially for extracurriculars, is not flat. Kids from the highest-earning families get higher extracurricular scores.

Here’s another chart that tells the same story. See that steeper orange line? That means a kid from a super-rich family gets more extracurricular points than an equally smart kid with less money.

The richest families can buy good extracurricular (and/or character or personal) scores for their kids. One of the ways they do that is by sending their kids to expensive feeder schools, as we will examine next week. I think another way is that they know which extracurriculars work. Not the yearbook, JV soccer team, or choir. But rather founding the right kind of NGO.

Close the extracurricular rating gap

How can you get the same boost in a non-academic rating for your kid? You can shrink the wedge between the green and orange lines by taking my online class on extracurriculars.

Super-rich families use class knowledge, private schools, and connections to learn which extracurriculars maximize admission odds. I know too. Harvard tried to keep a lot of internal documents produced in the lawsuit under seal, but I found them. I’ve read hundreds of pages of academic studies and firsthand accounts by admission officers. All of that information is distilled into actionable steps in the online class on extracurriculars.

If you’d like to discuss your child’s talents and goals more specifically, I’d be delighted to do a one-on-one Zoom call with your family. You can book those consultations here. I look forward to working with your family!