Feeder schools are real, part 2

We’re continuing our series examining the main lessons from this paper by Raj Chetty, David Deming, and John Friedman. Here are the previous posts:

How does income affect admission at elite schools?

State flagships do the right thing

Extracurriculars can broaden the path in

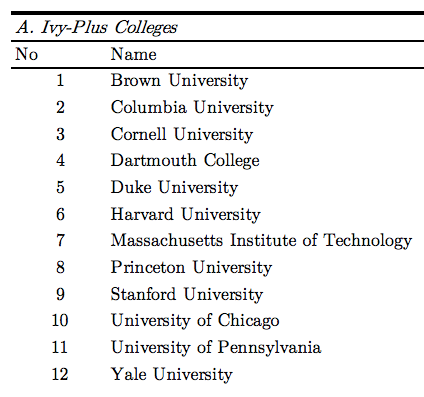

As a reminder, here are the colleges Chetty and his coauthors are talking about:

You may have heard of them!

Just the numbers we needed

This post will focus on feeder schools. I’ve written about feeder schools on this blog before:

“Here’s my main assertion: an applicant who attends a prestigious private school—especially one that sends many kids to the college in question— is likelier to get into a selective college than an applicant with the same grades, classes, test scores, and extracurriculars who does not go to a prestigious private school.”

In that earlier post, I acknowledged that I didn’t have numbers to back up this claim.

“The best evidence would be a regression for college admission results that includes a dummy variable for attending a private school. We could then know the marginal effect of just that one thing, separate from legacy status, parents’ income, GPA, etc. After all, lots of private school kids have rich parents, are legacies, play rich-kid sports, have carefully curated extracurriculars, etc. It is likely that those other variables are muddying the waters when we hear how 35 percent of a Harvard class or 27 percent of a Stanford class attended private school.”

The data gods heard my plea, because look what Chetty and his coauthors did! I’ve added the emphasis.

“To investigate the role of high schools more directly, we estimate high school effects on admissions and examine their association with academic and non-academic ratings. To do so, we regress an indicator for Ivy-Plus admission on high school fixed effects, controlling a quintic in test scores, and indicators for race, gender, and parental income group, excluding the student herself to avoid mechanical biases. The resulting high school fixed effects can be interpreted as the difference in Ivy-Plus admissions rates across high schools for students with comparable test scores and demographics.”

So now we can know the marginal effect of attending certain high schools. The authors didn’t include variables for individual schools but rather used these bins: poor public, rich public, religious private, secular private. Here are some examples.

And here’s what they found. Kids from rich public schools have the worst odds at super-selective colleges (5.3%). Kids from secular private schools have the best admission odds at those colleges (10.6%).

There’s the quantitative evidence for feeder schools that we were missing.

How do feeder schools help?

Chetty and his coauthors, bless them, don’t stop at quantifying the admission benefit that feeder schools give. They also examine how attending a feeder school affects admission.

Attending one of these high schools doesn’t boost the academic ratings that applicants get from admission offices. In fact, the middle- and upper middle-class strivers at rich public high schools like Paly and TJ are slightly likelier to get high academic ratings than the kids at Wherever Country Day.

Rather, the benefit from a feeder school is for non-academic ratings: the extracurricular and “character” ratings.

Applicants from secular private schools are much likelier to get high non-academic ratings. How do they get those higher ratings? We talked about choosing the right extracurriculars last week. Those admission-optimizing extracurriculars can look more or less flattering for an applicant depending on the letters of recommendation describing them.

Better letters

Chetty and his coauthors contend that teachers and guidance counselors at feeder schools send in more effective and flattering letters of recommendation. The x-axis for those two charts is a measurement of how feeder-y the high school is.

These charts support the commonsense understanding that teachers and counselors at private high schools, with their bosses leaning on them and with smaller caseloads than their counterparts at public schools, are likelier to write better letters. Now we have some good numbers to show it.

What does that mean for your kid?

If your kids attend a public high school in a prosperous area, you might look at that 5.3% admission rate above and feel queasy. Take heart! There are ways for your kid to get a good non-academic rating and flattering letters of recommendation too.

Choose extracurriculars that admission officers like. To find out what those are, you could take my online class on extracurriculars or book a one-on-one consultation.

Equip letter-writers with brag sheets that do most of the job for them. Reduce the cognitive load. To get my brag sheet templates and work together on filling them out for your kid, you can book a one-on-one consultation.

Ask letter writers plenty early, so no subconscious resentment about a last-minute hassle bleeds into their prose. The end of junior year is best.