Sara Harberson is wrong about peaking in high school

Let’s take a little break from Chetty. An old Latin teacher of mine used to talk about grammar poisoning. I don’t want to give anyone data poisoning. All the charts in this article are made up!

Sara Harberson is a prominent college admission counselor. I’m not trying to be mean to her personally but rather to examine her ideas.

She says you shouldn’t worry about peaking in high school:

“I clearly didn't ‘peak’ in high school. Most are in the same boat. It takes time to realize our fullest potential. Yet, my entire professional career is focused on working with high school students who want to peak right at that moment. […] They want to get admitted to the best college out there believing that will bring them fulfillment. They don't want to wait; they want to peak right now.”

This paragraph conflates “peaking” with “having the grades, test scores, and extracurricular accomplishments to get into a particular college.” We’re going to use “merit” as a shorthand for that combination of traits.

Peaking vs. clearing the hurdle

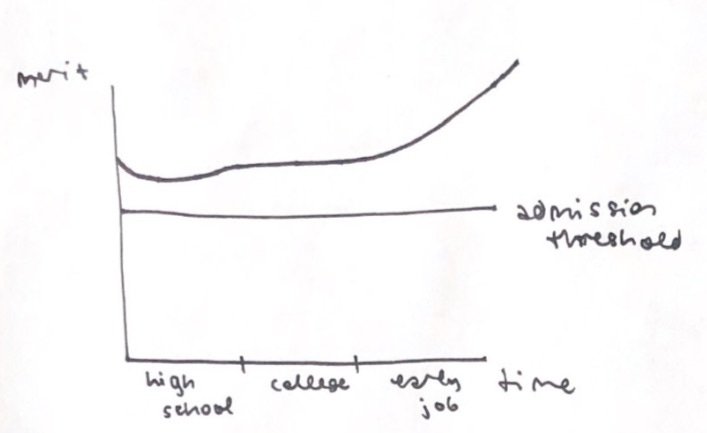

Harberson conflates two ideas: a kid reaching his or her highest degree of merit and having enough merit to get into College X. They’re different things. Let’s show that on some charts.

(These are not beautiful charts. If I hired a graphic designer, I’d have to pass the cost along to you. 😉 For any engineers reading, you just have to imagine some units for the merit axis.)

A kid could peak after high school and get over the admission bar:

A kid could peak in high school and not get over the admission bar:

Aim for a local maximum in sophomore and junior years

You might say: “That’s some very nice Algebra 2 pedantry. But shouldn’t my kid put her best foot forward?”

Yes! If your family is choosing to optimize for admission, your child should be hustling sophomore year and even more so junior year — and also the summer in between. That’s the time to:

load up on APs or IBs and get good grades in those classes (how many? take my class)

do the time-efficient test prep I recommend and take a standardized test a few times (for details, take my class)

commit to and excel in the kinds of extracurriculars admission officers like (which ones? take my class!)

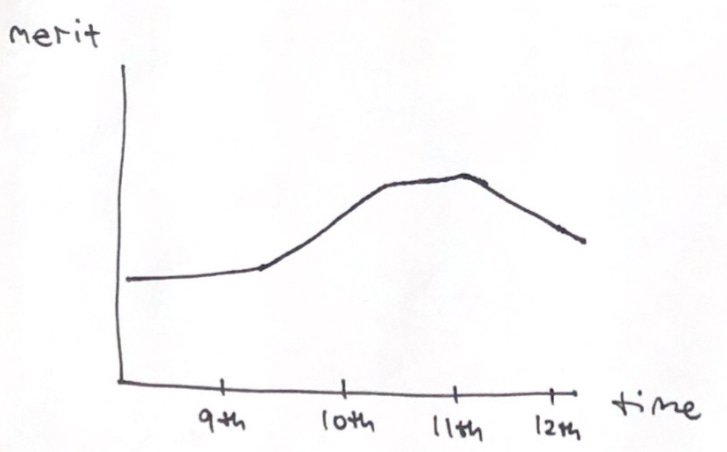

A local maximum is the top of a little bump in a line chart, but it isn’t the biggest bump in the whole thing. The global maximum is the biggest bump, hill, peak, whatever. Harberson doesn’t seem to get that distinction either.

Ideally, we put a little local maximum in during sophomore and junior years:

(That imaginary kid goes on to win a Nobel, so the global maximum is much higher.)

Why don’t I put that local maximum in senior year? Because the cake needs to be baked by the beginning of senior year to meet the early action and early admission deadlines.

Pick hurdles you can clear

One obvious lesson from these sloppy charts is that a student should not choose a college where his or her local maximum during high school falls short of the admission cutoff.

The clearest way to tell is with SAT or ACT scores. If your kid’s test scores are below the 25th percentile score at a given college, and he or she isn’t a recruited athlete or related to a major donor, it is unwise to apply there. Even if the school purports to be test-optional.

I realize I sound like a killjoy here, but I think gentle truth-telling is kinder than letting a kid waste time and effort or get attached to an impossible goal. The opportunity cost and heartbreak risk are too high.

In my online class on choosing colleges to apply to, I describe ways to compare your kid’s test scores to a college’s middle 50 (aka interquartile range) for test scores.

You can then choose if that college can be a safety, target, or reach school — or none of the above. You can sign up for that class here.

Analysis, not good vibes

Now I am going to be a little bit mean to Sara Harberson. Her college admission advising business is much more successful than mine, so I hope you won’t think I’m being too petty.

Let’s look at some excerpts from her blog post about peaking in high school:

“I understand now that our lives are enriched over time, after tremendous struggle, and with experiences, both triumphant and disappointing.”

“The long journey to the peak keeps us humble and hungry for more.”

“I hope I haven't peaked yet. I never want to coast down the mountain. The climb is so much more fulfilling.”

Yes, sure. But Hallmark sentiment doesn’t help parents or students make prudent decisions about college admission.

Harberson’s good-vibes approach is not unusual in this profession. A lot of the competition offers half-true reassurances and is reluctant or unable to distinguish between what is true and what they want to be true.

My service is not good vibes, though I do try to be empathetic as well as clear-eyed.

I have a clear and unsentimental view of colleges’ incentives. I know that colleges admit the kids who meet their needs—the kids who help colleges earn the most prestige and/or money. I offer actionable advice about aligning your child’s high school accomplishments with colleges’ aims. I draw conclusions from the best evidence available: documents and data revealed in litigation, academic literature, and firsthand accounts by admission officers. I choose quantitative evidence whenever possible and rigorously qualitative evidence when there aren’t numbers.

Sara Harberson has much more experience than I do, but there are no regression results on her blog.

If my approach appeals to you, consider booking a one-on-one session or signing up for one of my on-demand courses. I’d be delighted to work with your family!